The Danger of California's Drought

Alexandria Williams

In a summer which marked the hottest US temperature on record in Death Valley, and five wildfires ranking in the top six of California’s largest fires, a hot summer and dry winter forebode an even worse crisis as the state reels from the tragedies of the pandemic. While time seemed inconsequential during quarantine, seasons did pass, and they passed without water. With drought creeping in as water seeps out, California prepares for another devastational, possibly worse, fire season.

California Drought Monitor April 27th vs May 4th Image: United States Drought Monitor

The state has entered the second driest two year period on record, the last being 1976 and 1977, and the fourth driest year on record. Northern California received its first May red flag warning since 2014 as temperatures soar in the Sacramento region. Record breaking heat compounds the effects of dryness. Every dry year, “more water evaporates into the atmosphere as plants pump more water out of the soil to survive.”

Headlines of initial responses to drought are rippling across the state. States of emergency have been declared in two counties, Mendocino and Sonoma. Klamath Basin seeks economic disaster relief after only receiving 1/10 its usual acreage of water allocation. There are even talks between Marin Municipal Water District and East Bay Officials to build a pipeline across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, after Marin received the second least amount of rainfall in 143 years of record keeping.

With the previous fires still on Californians mind, severe drought paints an all too familiar picture. Unusually warm temperatures, “combined with very low precipitation and snowpack, extreme heat can lead to decreased streamflow, dry soils, and large-scale tree deaths”. These conditions turn “forests into matchsticks”, threatening an already dry, unmanaged environment.

“This one threatens to catch people by surprise who are exhausted by the events of the past year.” Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientist

A rising symbol in California’s battle against drought, Lake Mendocino, usually at 40% capacity this time of year, lies empty. Standing on the cracked earth of a dry lakebed, Gavin Newsom recently announced a drought state of emergency for the county.

Gavin Newsom at Lake Mendocino Image: Gavin Newsom Twitter

In 2018, the Mendocino Complex fire ravaged land north and west of Lake Mendocino, only to be recently usurped by the 2020 August Complex Fire as the largest in state history. With the potential and tendency for fire to burn within previous areas, known as burn-on-burn effects, Lake Mendocino’s drought is a warning for the state’s ravaged landscape.

“Oftentimes we overstate the word historic, but this is indeed a historic moment, certainly historic for this particular lake, Mendocino”. Gavin Newsom

Lake Orville 2017 after heavy rains vs April 2021 Image: Getty Images, Mercury News

In the previous drought of 2012–2016, Lake Orville symbolized California’s depleted water reserves, and remains to do so at 42% capacity, half its historic average. Lake Orville is the starting point of the State Water Project, a system of 21 dams and 701 miles of pipeline providing drinking water to 27 million people and irrigation to 750,000 acres of farmland. According to Mercury News, the Department of Water Resources announced the system is expected to deliver only, “5% of requested supplies this year”.

Melting snow from the Sierra Nevada's supplies Lake Orville, and 2020’s snowpack came in at 24%. With the Philip Snow Survey 2021 canceled due to dry weather conditions, and a state reliant on snowpack for 30% of the freshwater supply, water distribution becomes precarious.

California’s water use varies by region but 50% goes towards environmental, 40% agriculture, and 10% urban. The environment refers to, “water in rivers protected as “wild and scenic” under federal and state laws, water required for maintaining habitat within streams, water that supports wetlands within wildlife preserves”.

California Water Use Image: Department of Water Resources

Despite a commitment to preservation, in the driest years, water allocated to this sector is drastically reduced, as seen with the aforementioned Klamath Basin. For example, in a wet year such as 2006, 62% went to the environment and 29% to agriculture, while in a dry year, 2014, it switched dramatically to 28% and 61% respectively.

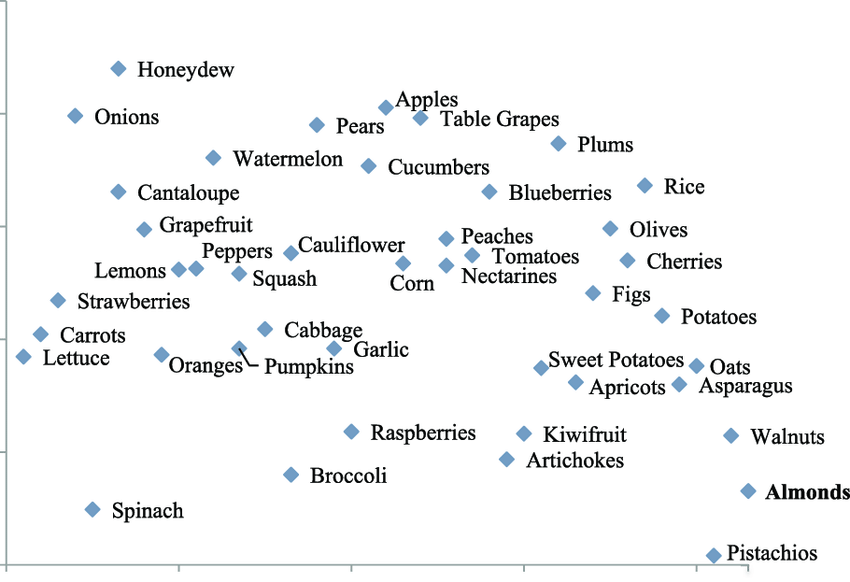

Farmers who plant heavy water reliant crops, referred to as high revenue perennial crops, are vulnerable to shortages such as these and consume a dwindling water supply. Almonds are notoriously known in California for devastatingly high water consumption. Requiring daily watering all year long, tree nut acreage between 2008 and 2018 has increased by 85%. Almonds, walnuts, and pistachios are three of California’s most water intensive crops, and ironically, provide the least nutritional value.

Major California crops ranked by water footprint values (horizontal) and nutrient value (vertical) Image: Research Gate Fulton and Norton

Increased reliance on groundwater to maintain consistent daily watering through a drought threatens already depleted reserves. During the 2012–2016 drought, the Central Valley sank upwards of 60 cm per year. While the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act passed in 2014 stabilized groundwater usage, it allows for increased pumping during a drought. Given California has been embroiled in a decades long megadrought since 2000, the dangers of a sinking Central Valley are rapidly progressing.

Groundwater Losses in California during wet and dry seasons Image: Jay Familglietti/NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

With so much to manage from wildfires to groundwater depletion to threats of aquatic species extinction, what is being done. In April, Governor Newsom announced a $536 million plan to improve forest management and thin out vegetation. With a portion allocated to homeowner grants for home protection, Newsom earlier used $81 million to hire 1,400 more firefighters.

As for the drought, California Senate democrats presented a $3.4 billion proposal to bolster ongoing drought resiliency projects. Included in the hefty sum is $1 billion to pay off unpaid water bills, $285 million to protect fish and wildlife, and $500 million to provide emergency water access to smaller communities.

However, long floating throughout media channels and academic discourse has been the call for a return to indigenous practices to maintain forest floors and prevent rampant fire damage. According to multiple news sources, Newsom is currently in talks with tribes on how to implement “intentional burnings”, with a recently published Good Fire Report providing a policy roadmap.

Released in the end of March by the Karuk Tribe, the report provides, “the legal and policy underpinnings of current barriers to expanding the scope of intentional fire in California”, while identifying specific policy solutions. The barriers appear more complex than anticipated as air quality permits and burn permit programs actively push against intentional burnings. Additionally, California’s simple negligence standard looms over tribal members, threatening financial ruin for the rare escaped fire.

Just as, “Californians Know … Water Conservation Is For Life”, forest management is also for life. A more proactive citizenship is required as Climate Change intensifies the effects of drought each year. The states’ Save Our Water Campaign offers guides and how-to’s for good water saving habits. Taking five minute showers and washing only full loads of laundry are popularly advertised. Whether popularity for gardening in COVID grew out of self-sufficiency, or sheer boredom, opportunity for conservation also lies within the soil. Recycling indoor water and composing to increase soil’s capacity to hold water saves 30% of water. It takes a lot of blue to stay green, and our planet needs it now more than ever.